A real-life horror story – 15 years in hell with unimaginable pain!

New Diagnosis – Slipping Rib Syndrome

Slipping rib syndrome, in which one or more of the lower ribs becomes detached and results in pressure or irritation to the surrounding nerves, causes severe pain with every breath or movement. This often misdiagnosed condition can lead to an inability to go to work or school and withdrawal from normal activities.

“This is an obscure diagnosis that a lot of people don’t know about,” Dr. Hansen said. “These patients are in debilitating pain and often suicidal. After this procedure, their pain is like night and day. Within a week after the repair, their lives are turned around. They have hope, and they are not considering ending their own life because of the pain anymore.”

–

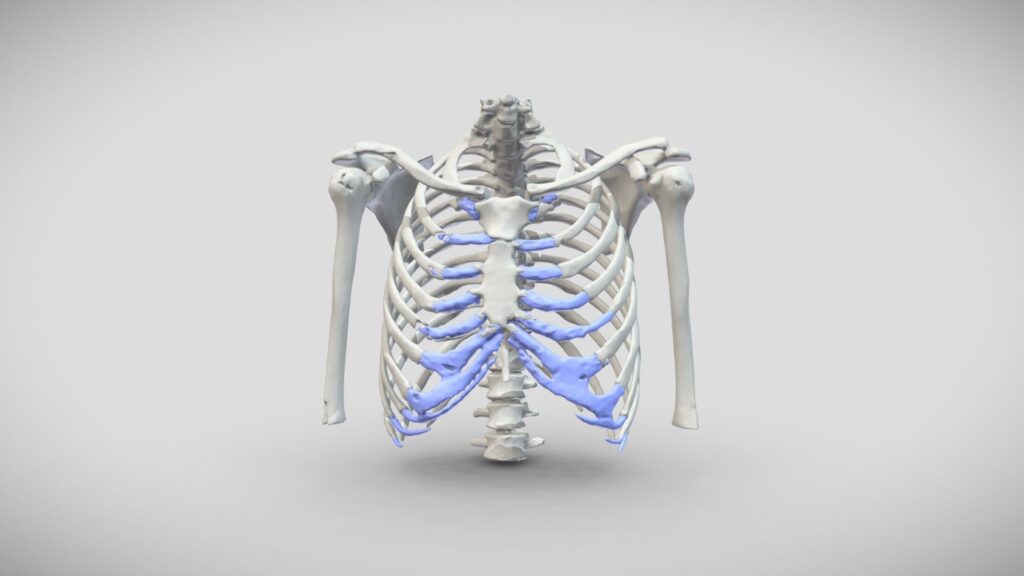

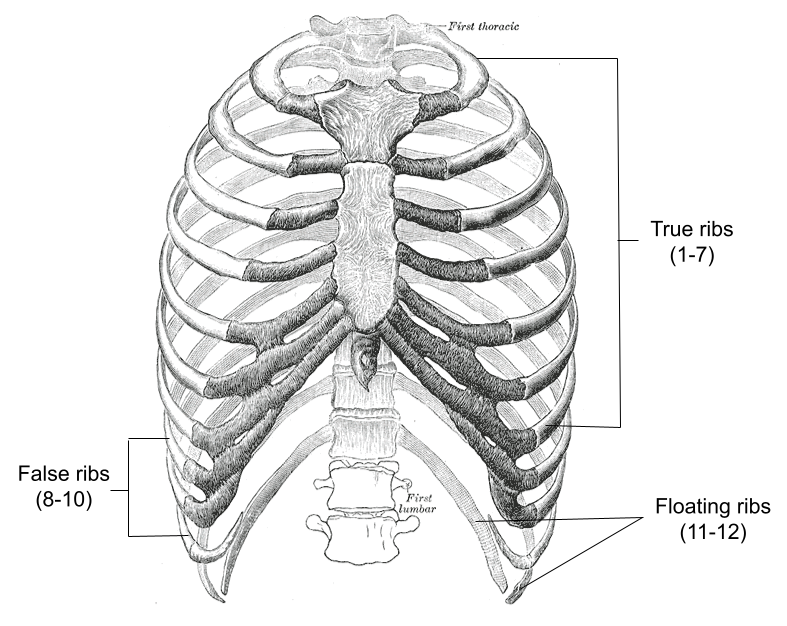

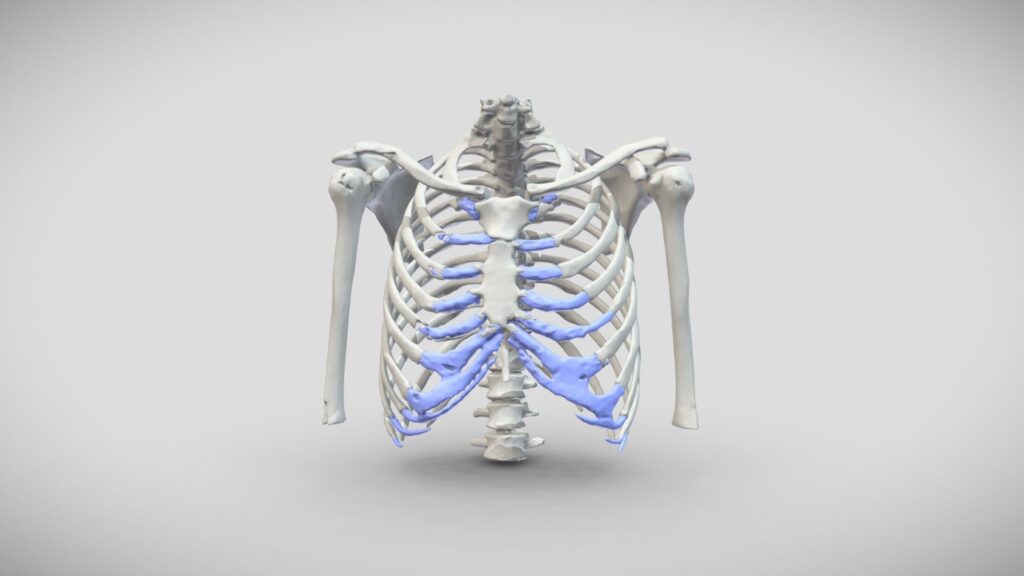

What you seen in blue above is costal cartilage. It connects ribs 8, 9 and 10 (the “false” ribs) to the costal cartilage of the 7th rib, which then connects directly to the sternum. Here’s an example of a costal margin that is pretty beat up. I suspect mine looks similar. You can sort of see mine if you click here.

It has taken me 15 years to diagnose my horrific chronic pain but I finally discovered I have Slipping Rib Syndrome. The knife in my back is where 90% of my pain is. I do have painful ribs along the intercostal nerves and that knife does turn into a spear that goes all the way through to the xiphoid and left costal margin, when flared up. Mid-back pain is a common symptom of SRS but the million dollar question is, is SRS the cause of my back pain? It’s not a fun surgery and people feel worse before they feel better. It can take years to heal from it. If I knew it was the solution, I wouldn’t hesitate. My life isn’t worth living so what do I have to lose? I’m driving myself crazy second-guessing this new finding but hopefully Dr. Hansen, who I see in August, can reassure me that it is indeed my problem and that I should move forward with the surgery.

I managed to generate a 3-D image from my CT scan using Zoros. I’ll work on generating more.

I am a chronic pain patient who has been in severe pain, almost constantly, for 15 years. This pain has stolen my life, taken my friends, cost me my job and independence and now has me bedridden with intense, stabbing pain. I feel like someone has a voodoo doll of me and I am being tortured. It’s a nightmare I never could have imagined. However just recently, 15 years after it all began, I believe I have solved the mystery. I have diagnosed myself with Slipping Rib Syndrome (using the “hooking maneuver”) and it has been verified by the only imaging capable of identifying it, dynamic ultrasound, performed by a doctor familiar with the condition.

I was an extreme sports athlete for decades and I always assumed the body would heal itself, so I crashed constantly and treated my ribcage like a piñata. I got away with this, having a lot of fun, with minor aches and pains (other than blowing out my left ab muscle in my 40s which was probably the beginning of everything), until the age of 50 when I got a pain in my mid-back, on the left side, about an inch from the middle of my spine. It began as a tight feeling with pain when I twisted or bent. Over the next few weeks it would become a stabbing, burning pain with an intensity that I’d never experienced before. I thought I was immune to pain, constantly living with sports injuries, but this was something different – it wouldn’t heal! It only got worse. This was before the DEA’s war on pain patients so I was prescribed copious amounts of opiates, none of which touched the pain. Until a pain expert at UCSF suggested methadone which is good for nerve pain. It’s always felt nervy, like a major nerve is being stabbed or irritated (I now have reason to believe it’s a rib irritating an intercostal nerve). That turned out to be the only thing we’ve found that is effective at controlling my pain. Lasers, magnets, PRP, corticosteroid injections, nothing “therapeutic” seems to help. In fact after 15 years, my muscles and nerves are so irritated that they are sore to the touch and any palpation or movement seems to just further irritate the constantly irritated nerves. You can see the inflammation on my left back, creating blobs of pain. Breathing, eating and moving are irritants and I’ve been saying for years that because this is a structural issue, only surgery will end my suffering. That is proving out to be true. Getting past the roadblock of doctors to see a thoracic surgeon has been its own nightmare. I’ve been gaslighted, ignored, marginalized and insulted by so many doctors it’s hard to not be angry. However I realize it’s not their fault. It’s just human nature to ignore or minimalize other people’s pain and doctors are only human. Studies show that they lose most of their capacity for empathy by their 3rd year of medical school. It’s the system that’s broken and the system makes their lives difficult too. I’m grateful to the doctors that have helped me and I try not to be angry at those that didn’t, for whatever reason. While my condition is not rare (just underdiagnosed), most doctors have never heard of it. This is changing now that patients have access to the internet. Most cases of SRS are self-diagnosed.

Slipping Rib Syndrome goes by many names (and there are many similar conditions like rib-tip and rib-head syndromes) but the medical term is interchondral subluxation. I think in my case, it’s a result of hypermobility and repeated trauma to my rib cage, possibly also my wrecked left core muscles and surgeries. I was somewhat familiar with SRS but dismissed it years ago because I didn’t have clicking ribs or really much rib pain at all, or so I thought. That’s why it has taken me so long to figure it out. It is very common for SRS to be felt in the back and chest. Here is a video of Dr. Hansen describing the symptom as a “spear from the mid-back to the xiphoid process”. Those were my words exactly! I’ll get into why that is and why I believe I have SRS and why I think it is the cause of my chronic pain. Actually that’s what this whole website is about. Thank you for being here.

What if I have SRS but it’s not what’s causing the knife in my back?

This is my biggest concern. At 51:23 of this video, Dr. Hansen expresses concern about diagnosing SRS when it doesn’t hurt at the dislocation point of the slipped rib. That’s me and it’s why it took me so long to suspect SRS. It just doesn’t hurt that much at the point of rib dislocation.

What are the alternatives?

- Costotransverse Joint Dysfunction – ground-zero of my pain seems to be at or near the left 10th costotransverse joint. My main concern about this SRS diagnosis is that it doesn’t hurt at the points of rib-tip dislocation.

- Facet Joint Syndrome – I did rush into a Z-joint nerve ablation at T9/10 or T10/11 out of desperation many years ago (with mixed results). From Health Central, “When a rib slips at T10 or T11, there is an opportunity for facet joint involvement. If this occurs, you can experience considerable pain.” Could this be causing the knife in my back?

- I blew a hole through the middle of my rectus abdominis around 2000. I got surgery in 2003 but because it was a clean tear through the middle of the muscle, the surgeon just stitched it up. I proceeded to rib those stitches out almost immediately with windsurfing in the Columbia River Gorge. I had surgery again in 2019 which revealed significant, long-term damage requiring mesh and diastasis repair. So my left core muscles have been through hell and are still sore. A study suggesting a weak/damaged rectus abdominis connection means my blown out left ab muscle could be connected as well. Unfortunately my story goes back 30 years and includes a lot of physical damage, making a complete understanding of everything almost impossible. Could this be causing the knife in my back?

- A Stanford radiologist who specializes in imaging for pain did an experimental scan on me using a different radiotracer, FTC, but one that behaves very similar to FDG. This showed a number of osseous issues, suggesting an auto-immune illness. Namely abnormal uptake in the vertebral marrow of T9-12 and the costotransverse/costovertebral joints. He felt the vertebral uptake was a significant pain generator. What if osteitis from my autoimmune illness is causing the knife in my back?

This costal cartilage reconstruction surgery, while called minimally invasive, is no joke. It’s a long, painful recovery and my nerves are already on fire. I suppose I’m desperate enough to try anything but I hope this is a light at the end of the tunnel and not an oncoming train.

I injured my back in the 1990s playing volleyball that took years to resolve. My vague memory tells me the feeling was similar to this pain, just not nearly as bad. More of an ache. Was the 9/10 facet joint disfunction the correct diagnosis back in 2011? What about the ablation? Perhaps the ablation damaged the joint. Is joint pain from the tendons of that joint? Could my 10th costotransverse or costovertebral joint be subluxated? What about my two rectus abdominis surgeries, one in 2003 and another in 2019? I’m pretty sure I’ll need costal margin reconstruction surgery. Will that address my back pain?

Whenever I’m in doubt I just watch this.

I have an appointment with Dr. Adam Hansen (the guru for this condition) in West Virginia on August 12th. I am counting the days!

The rest of this page is just basics on the condition. I will “borrow” some material from other sources and highlight parts that are relevant to my case or especially interesting. This website is a bit of a mess and needs to be cleaned up. It’s not for the public. It’s for myself and my doctors if any of them are inclined to read it (I’m not holding my breath). I hope to eventually turn it into something to help others but for now it’s mostly about me, (although the rest of this page isn’t 🙂 )

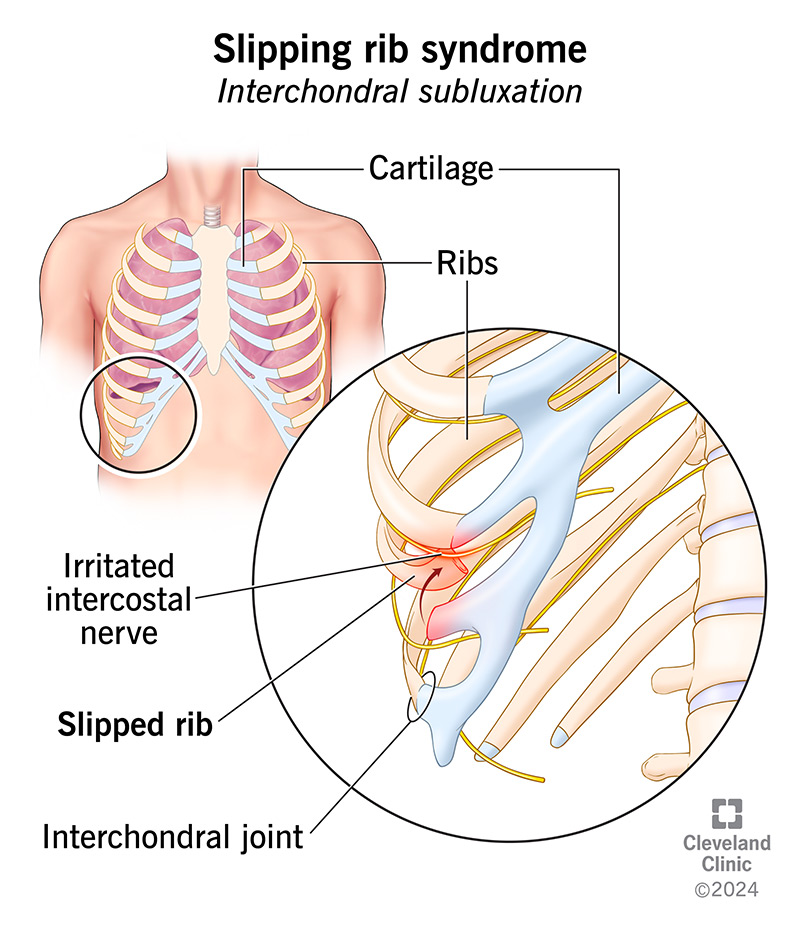

from the Cleveland Clinic….

Slipping Rib Syndrome

Slipping rib syndrome happens when one of your lower ribs partially dislocates, slipping in and out of place and sometimes trapping the nerve beneath it. It can cause intense episodes of pain that may spread or be hard to pin down. Diagnosis can be difficult unless your healthcare provider is already aware of the syndrome.

Overview

Slipping rib syndrome is a little-known cause of musculoskeletal chest pain that comes and goes. It comes on suddenly and severely before tapering off. Sometimes there’s a popping or clicking sensation with it.

It happens when the cartilage that attaches two of your lower ribs together loosens or becomes unstable. This causes one of the ribs to slip in and out of place, irritating your intercostal nerve.

Slipping rib syndrome goes by many other names. Just a few of them include displaced rib, clicking rib syndrome, floating rib syndrome, gliding rib syndrome, rib-tip syndrome and Cyriax syndrome.

The medical term is interchondral subluxation. Subluxation is a partial dislocation of a joint. Your interchondral joints are where the cartilage (chondral) tips of your lower ribs connect to the rib above.

How common is this condition?

Recent data suggests that slipping rib syndrome accounts for about 5% of all cases of chest wall pain. Unfortunately, not all healthcare providers are aware of the condition, so it often goes undiagnosed.

What is slipping rib syndrome?

Slipping rib syndrome is a little-known cause of musculoskeletal chest pain that comes and goes. It comes on suddenly and severely before tapering off. Sometimes there’s a popping or clicking sensation with it.

It happens when the cartilage that attaches two of your lower ribs together loosens or becomes unstable. This causes one of the ribs to slip in and out of place, irritating your intercostal nerve.

Slipping rib syndrome goes by many other names. Just a few of them include displaced rib, clicking rib syndrome, floating rib syndrome, gliding rib syndrome, rib-tip syndrome and Cyriax syndrome.

The medical term is interchondral subluxation. Subluxation is a partial dislocation of a joint. Your interchondral joints are where the cartilage (chondral) tips of your lower ribs connect to the rib above.

How common is this condition?

Recent data suggests that slipping rib syndrome accounts for about 5% of all cases of chest wall pain. Unfortunately, not all healthcare providers are aware of the condition, so it often goes undiagnosed.

Symptoms and Causes

What does a slipping rib feel like?

When your rib first slips, the pain can feel sudden, sharp and stabbing. You may feel or hear your rib “clicking” or “popping” as it moves across your other rib. After that, the pain may linger as a dull ache.

Most people notice this pattern repeating over time. Your rib might slip when you cough or sneeze or move in a certain way. Even something like reaching overhead or rolling out of bed might trigger it.

A slipping rib can irritate the intercostal nerve that runs between your ribs. This probably triggers the sharp, localized pain you feel at first. Eventually, it may also inflame the soft tissues around your rib.

This may cause a more diffuse type of pain that’s harder to locate in one place. It might feel like lower chest pain or upper abdominal pain. Sometimes, it radiates to your upper back or one of your flanks.

Which ribs does slipping rib syndrome affect?

You have twelve ribs, numbered from top to bottom. Slipping rib syndrome affects ribs eight through ten. These are called your “false ribs,” because they don’t attach directly to your breastbone (sternum).

Instead, each false rib attaches to the rib above it. These attachment sites, made of cartilage, are your interchondral joints. Weakening of one of these joints causes one of your false ribs to slip out of place.

The terms “floating rib syndrome” and “floating rib pain” are misnomers for slipping rib syndrome. Your “floating ribs” are your bottom ribs eleven and twelve. These ribs don’t have interchondral joints.

They’re called “floating ribs” because they don’t attach to your breastbone or your other ribs, only to your spine. These ribs can’t “slip” in the same way. But you may feel pain in the tissues around them.

What causes slipping rib syndrome?

Your rib slips when the cartilage at the interchondral joint is weakened or displaced. This might happen suddenly or gradually. In some cases, it might be present at birth. Possible contributing causes include:

- Congenital weakness (birth defect)

- Joint hypermobility (when your joint or joints have an abnormally wide range of motion)

- Overuse of your joints (repetitive strain injury)

- Traumatic injury (such as an accident or sports injury)

Diagnosis and Tests

How do you test for slipping rib syndrome?

A healthcare provider investigating your pain will often start by taking images, like a chest X-ray or CT scan. But a slipping rib usually won’t show up in still images. Your provider will need to see it in action.

One way it might show up is on a dynamic ultrasound — an ultrasound taken while you perform certain movements. Twisting, coughing, the Valsalva maneuver, or others might make your rib slip in real time.

But if your healthcare provider already suspects slipping rib syndrome, they can check for it during a physical exam. They do this by reproducing your symptoms with a test called the “hooking maneuver.”

For this simple test, your provider hooks their fingers under the lower boundary of your ribcage and gently lifts it upward. This reproduces the pain of slipping rib syndrome, and sometimes the pop or click.

Management and Treatment

How do you fix a slipping rib?

Sometimes, a slipping rib heals on its own. If it’s not bothering you too much, your provider might suggest waiting and watching to see if it does. They’ll suggest conservative treatments to ease your pain, like:

- Hot/cold therapy

- Over-the-counter pain medications, like NSAIDs

- A period of rest, followed by physical therapy

If this approach isn’t working, they might suggest an intercostal nerve block — an injection of medication to calm your irritated nerve. This provides temporary relief, and sometimes it helps the healing process.

Surgery

If your symptoms don’t improve over the long term, you might need surgery to fix slipping rib syndrome. Surgeons use minimally invasive methods, like video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), whenever possible.

Surgery to fix a slipping rib might mean:

- Tightening or repairing loose ligaments or cartilage with stitches (stabilization)

- Removing the damaged or detached cartilage tip (partial rib resection)

- Using metal plates to separate ribs that are sliding together (rib plating)

Outlook / Prognosis

What can I expect if I have this condition?

Getting a diagnosis for slipping rib syndrome is half the battle. Once your healthcare provider recognizes the condition, healing can begin. Many people find relief over time through conservative treatments.

Not everyone will need surgery for slipping rib syndrome, but surgery is usually successful if you do. Occasionally, there’s an unrecognized cause that leads to symptoms returning later in another rib.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

Slipping rib pain can be intense, confusing and frightening, especially when your healthcare provider can’t explain it. It’s incredibly frustrating to have chronic pain with no diagnosis or treatment plan.

Fortunately, awareness of slipping rib syndrome is gradually increasing. And for all its mystery, it’s not an incurable or life-threatening disease — just an anatomical issue that surgery can fix.

from Wikipedia…

Slipping rib syndrome

Slipping rib syndrome (SRS) is a condition in which the interchondral ligaments are weakened or disrupted and have increased laxity, causing the costal cartilage tips to subluxate (partially dislocate). This results in pain or discomfort due to pinched or irritated intercostal nerves, straining of the intercostal muscles, and inflammation. The condition affects the 8th, 9th, and 10th ribs, referred to as the false ribs, with the 10th rib most commonly affected.

Slipping rib syndrome was first described by Edgar Ferdinand Cyriax in 1919; however, the condition is rarely recognized and frequently overlooked. A study estimated the prevalence of the condition to be 1% of clinical diagnoses in a general medicine clinic and 5% in a gastroenterology clinic, with a separate study finding it to be 3% in a mixed specialty general medicine and gastroenterology clinic.[1][2]

The condition has also been referred to as Cyriax syndrome, clicking rib syndrome, painful rib syndrome, interchondral subluxation, or displaced ribs. The term “slipping rib syndrome” was coined by surgeon Robert Davies-Colley in 1922, which has been popularly quoted since.

Symptoms

The presentation of slipping rib syndrome varies for each individual and can present at one or both sides of the rib cage, with symptoms appearing primarily in the abdomen and back.[3] Pain is most commonly presented as episodic and varies from a minor nuisance to severely impacting quality of life.[1][4] It has been reported that symptoms can last from minutes to hours.[3][5]

One of the commonly reported symptoms of this condition is the sensation of “popping” or “clicking” of the lower ribs as a result of subluxation of the cartilaginous joints.[1][3] Individuals with SRS report an intense, sharp pain that can radiate from the chest to the back, and may be reproducible by pressing on the affected rib(s).[4][6] A dull, aching sensation has also been reported by some affected individuals.[3] Certain postures or movements may exacerbate the symptoms, such as stretching, reaching, coughing, sneezing, lifting, bending, sitting, sports activities, and respiration.[1][3][4] There have also been reports of vomiting and nausea associated with the condition.[7]

Risk factors

The causes of slipping rib syndrome are unclear,[8] although several risk factors have been suggested. The condition often accompanies a history of physical trauma. This observation could explain reports of the condition among athletes, as they are at increased risk for trauma, especially for certain full-contact sports such as hockey, wrestling, and American football.[7] There have also been reports of slipping rib syndrome among other athletes, such as swimmers, which could plausibly result from repetitive upper body movements coupled with high physical demands.[3][9]

Reported incidents, in which no history of traumatic impact to the chest wall has been described, are considered a gradual onset condition.[8] Slipping rib syndrome may also result from the presence of a birth defect, such as an unstable bifid rib.[9] Generalized hypermobility has also been suggested to be a possible further risk factor.[3]

Diagnosis

Diagnosing slipping rib syndrome is predominantly clinical,[10][11] with a physical examination of the affected rib being the most commonly utilized. A technique known as the “hooking maneuver” is commonly used amongst medical professionals to diagnose slipping rib syndrome. The examiner will hook their fingers under the costal margin, then pull in an anterior (outward) and superior (upward) direction, with a positive result when movement or pain is replicated during this action.[7]

Plain radiographs, CT scans, MRI, and standard ultrasound, are all unable to visualize the cartilage affected by SRS; however, they are often used to exclude other conditions.[3] Dynamic ultrasound is occasionally used to evaluate the dynamic laxity or displacement of the cartilage;[10] however, it has been said to be not much superior to that of a physical examination from an experienced physician, as a diagnosis is dependent on the technician’s expertise and knowledge of the condition.[9] A positive result of a dynamic ultrasound for slipping rib syndrome requires an observed subluxation of the cartilage, which may be elicited with the Valsalva, crunch, or other maneuvers.[12][13] Nerve blocking injections have also been utilized as a diagnostic method by noting the absence of pain following an injection to the intercostal nerves of the affected ribs.[14][11]

Differential diagnosis

Slipping rib syndrome is often confused with costochondritis and Tietze syndrome, as they also involve the cartilage of the thoracic wall. Costochondritis is a common cause of chest pain, consisting of up to 30% of chest pain complaints in emergency departments. The pain is typically diffused with the upper costochondral or sternocostal junctions most frequently involved, unlike slipping rib syndrome, which involves the lower rib cage. Tietze syndrome differs from these conditions as it is often associated with inflammation and swelling of the costochondral, sternocostal, and sternoclavicular joints, whereas individuals with slipping rib syndrome or costochondritis will exhibit no swelling. Tietze syndrome typically involves the second and third ribs and is usually a result of infectious, rheumatologic, or neoplastic processes.[6]

A condition referred to as twelfth rib syndrome is similar to slipping rib syndrome; however, it affects the floating ribs (11–12) which do not have any attachments to the sternum. Some researchers classify slipping rib syndrome and twelfth rib syndrome into a group referred to as painful rib syndrome, others classify twelfth rib syndrome as a subtype of slipping rib syndrome, and some considering the two to be separate conditions altogether. The two disorders have different presentation and diagnostic criteria, such that a diagnosis for twelfth rib syndrome does not include the hooking maneuver and typically presents as lower back, abdominal, and groin pain.[15]

Other differential diagnosis includes pleurisy, rib fracture, gastric ulcer, cholecystitis, esophagitis, and hepatosplenic abnormalities.[4]

Treatment

Treatment modalities for slipping rib syndrome range from conservative measures to surgical procedures.

Conservative measures

Conservative measures are often the first forms of treatment offered to patients with slipping rib syndrome, especially those in which symptoms are minor.[16] Often the patients will be reassured and recommended to limit activity, use ice, and take pain medication such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).[4] Further measures such as osteopathic manipulation treatment (OMT), physical therapy, chiropractic treatment, and acupuncture, are other non-invasive methods that have been used to treat SRS, with the goal of these treatments typically being relief or symptom management. Topical medications are occasionally used, such as Diclofenac gel and lidocaine transdermal patches, which have been noted to provide temporary relief of symptoms.[3][11]

Nerve blocking injections

Minimally invasive procedures have been used for individuals with moderate slipping rib syndrome.[4] Nerve blocking injections consisting of steroidal or local anesthetic agents have been commonly reported as a treatment to avoid surgical intervention.[4][8] This minimally invasive intervention is seen as temporary, with repeated injections necessary to prevent the resurgence of symptoms.[4][11]

Surgical procedures

Surgical intervention is often performed in cases where other treatment modalities have failed to provide a solution.[7][11] There are four types of surgical procedures noted in current literature: costal cartilage removal, rib resection, laparoscopic costal cartilage removal, and rib stabilization with plating.[1]

Costal cartilage removal, or excision, was first attempted in 1922 by Davies-Colley and has been the technique used by several surgeons since then. This method of surgical repair includes removal of the cartilage affected from the sternum to the boned portion of the rib, with or without preserving the perichondrium. Rib resection differentiates from costal cartilage removal as it removes a small bone portion of the affected rib(s).[1] Laparoscopic costal cartilage removal is a minimally invasive, intra-abdominal approach to treating the condition. The affected cartilage is excised from the sternocostal junction to the costochondral junction.[17] It is to be noted that within studies that have performed these procedures, some individuals may experience recurrence of symptoms.[1]

An alternative technique known as rib stabilization with plating is used to prevent subluxation of the affected rib(s) while preserving thorax mobility. It was first used to treat individuals who have undergone previous resection surgeries but experienced a recurrence of symptoms. In this procedure, the ribs are stabilized using a bio-absorbable plate that is anchored onto a stable non-affected rib located above the affected rib(s). The plates are vertically placed onto the ribs and secured using non-absorbable sutures.[1][18]

A more recent technique of rib stabilization with suturing, colloquially known as the Hansen Method after its creator, is used to bring the affected rib(s) to their normal anatomy. The method uses an orthopedic tape suture to tie the slipped rib around a higher, unaffected rib(s) to stabilize it. This method is similar in concept to the aforementioned method of stabilization with plating; however, the suture is not bioabsorbable.[19]

Epidemiology

Slipping rib syndrome is considered to be underdiagnosed and frequently overlooked.[1][20] Past literature has noted the condition to be rare or uncommon, but one 1980 study estimated SRS to have 1% of clinical diagnoses in new patients at a general medicine clinic and 5% at a specialty gastroenterology clinic, with the prevalence being even higher for patients referred to the specialty clinic after multiple negative investigations.[1][21] A separate study from 1993 found that slipping rib syndrome accounted for 3% of new referrals to a mixed specialty general medicine and gastroenterology clinic.[2]

It is unclear whether SRS is more common in women as some studies report an equal gender distribution while others report the condition to occur more often in females.[1][2][21] It has been suggested by some researchers that there is a hormonal connection between hormones and the increased ligament laxity observed in females during pregnancy, though this theory has yet to be upheld or explored.[11]

History

Slipping rib syndrome was first mentioned in 1919 by Edgar Ferdinand Cyriax, an orthopedic physician and physiotherapist, who described a chest pain associated with a “popping” or “clicking” sensation.[9][22] The condition was originally named after him, Cyriax syndrome, but has used multiple names since then, including clicking rib syndrome, painful rib syndrome, interchondral subluxation, and displaced ribs.[23] The name “slipping rib syndrome” was first used by surgeon Robert Davies-Colley and gained popularity, becoming the most commonly quoted term for the condition.[8] Davies-Colley was also the first to describe an operation for slipping rib syndrome, a costal cartilage removal.[3][24]

The “hooking maneuver” was noted in 1977 by Heinz & Zavala to be useful for slipping rib syndrome as an accurate diagnostic method.[4][25]

From the RIb Injury Clinic

Slipping Rib Syndrome

Slipped rib syndrome was first described in the early 1900’s by Cyriax and is an underdiagnosed and often poorly understand condition of the costal arch or margin. It’s caused by excessive movement of the anterior cartilaginous part of the lower ribs as they ‘join’ the costal arch. The excessive movement or hypermobility of the anterior part of the ribs, typically the 8th, 9th or 10th rib is probably caused by either congenital or acquired (following a minor injury or repetitive strain) disruption of the fibrous junctions of these ‘false’ ribs at the costal arch, allowing the tips of the ribs to move or slip under the rib above. The movement causes lower rib or upper abdominal pain.

Symptoms

The pain is caused by excessive movement of the lower rib tips as they pass under the costal arch (what is sometimes called subluxing). It may be associated with a reported clicking or popping sensation. The pain is typically with certain movements or activities usually involving twisting, bending, deep breathing (so may come on after exercise) or even sneezing or coughing. The pain is often intermittent and sharp when the rib tip is moving excessively but can also be more like a dull ache particularly after an activity that ‘triggers’ movement. Resting, avoiding certain activities or even stretching out the rib cage can alleviate the pain.

Slipped rib syndrome tends to be one-sided though can affect both sides, tends to affect younger patients though any age can be affected and seems to be more common in certain sports or recreational activities such as swimming. Previous rib injury may lead to a form of acquired Slipped Rib Syndrome. Hypermobility and joint laxity also appear to be linked as does the presence of rib flare and other chest wall problems such as pectus deformities.

Investigations

Diagnosis of Slipped Rib Syndrome can often be difficult due to the nature of the pain and the many other chest or abdominal conditions that can cause pain in this part of the body. Seeing a doctor who is familiar with Slipped Rib Syndrome is important in assessing and investigating the condition. Clinical examination may relieve tenderness over the area and occasionally the hypermobile rib tip can be palpated and if moved can generate the pain (the Hook Maneuver).

Patients may have had multiple investigations already and often Chest CT or even MRI tends not to be helpful. Dynamic Ultrasound with a radiologist experienced with Slipped Rib Syndrome is essential and often allows the radiologist to demonstrate excessive movement of the rib tip affected.

Investigations

Diagnosis of Slipped Rib Syndrome can often be difficult due to the nature of the pain and the many other chest or abdominal conditions that can cause pain in this part of the body. Seeing a doctor who is familiar with Slipped Rib Syndrome is important in assessing and investigating the condition. Clinical examination may relieve tenderness over the area and occasionally the hypermobile rib tip can be palpated and if moved can generate the pain (the Hook Maneuver).

Patients may have had multiple investigations already and often Chest CT or even MRI tends not to be helpful. Dynamic Ultrasound with a radiologist experienced with Slipped Rib Syndrome is essential and often allows the radiologist to demonstrate excessive movement of the rib tip affected.

Occasionally if the diagnosis is less clear cut, diagnostic local anesthetic injection to the intercostal nerves corresponding to the rib tip involved can help confirm likely Slipping Rib Syndrome. Using Local anesthetic block with or without corticosteroid may give temporary relief and occasionally complete relief of discomfort and can be considered as a potential treatment option.

Treatment

Establishing the diagnosis with a careful clinical history and examination together with a focused dynamic ultrasound scan allows a discussion with the patient different options and often a simple recognition and reassurance of the problem may be enough. Taking a conservative approach is acceptable once diagnosed and would include avoidance of activity aggravating pain, rest, NSAIDS and occasionally ‘manipulative’ physical therapy techniques may all help. If conservative treatment is not helping a trial of local anesthetic with or without corticosteroid may be considered.

Surgery remains a good treatment with reports of excellent outcomes though recurrence of the pain has also been described. Typically, through a small targeted incision, the mobile rib tip is delivered from under the costal arch and excised. Alternately, the slipping rib can be stabilized to prevent slippage. See Surgery Treatment